After the death of William Tyndale, publication of the Bible in English began to escalate rather quickly. David Daniell estimates that from 1525 to 1640, printed English Bibles numbered over two million – and this for a population in England of only about six million. The popular demand was enormous!

However, as the English translation of Holy Scripture gained legal and societal acceptance, there was a downside. The powers that be hijacked the enterprise to their own ends. As Bibles in the English language gained mainstream status, the whole process of how the Bible was packaged reflected the “Church of England” bureaucracy or tributes to royal power. As persecution of dissenters eventually subsided in England, the radical commitment attached to owning a Bible also diminished, especially as many of the most committed separatists and dissenters headed for the New World. The eventual publication of the King James Version was a major accomplishment, but its biggest influence was felt across the Atlantic in America.

Matthew’s Bible (1537)

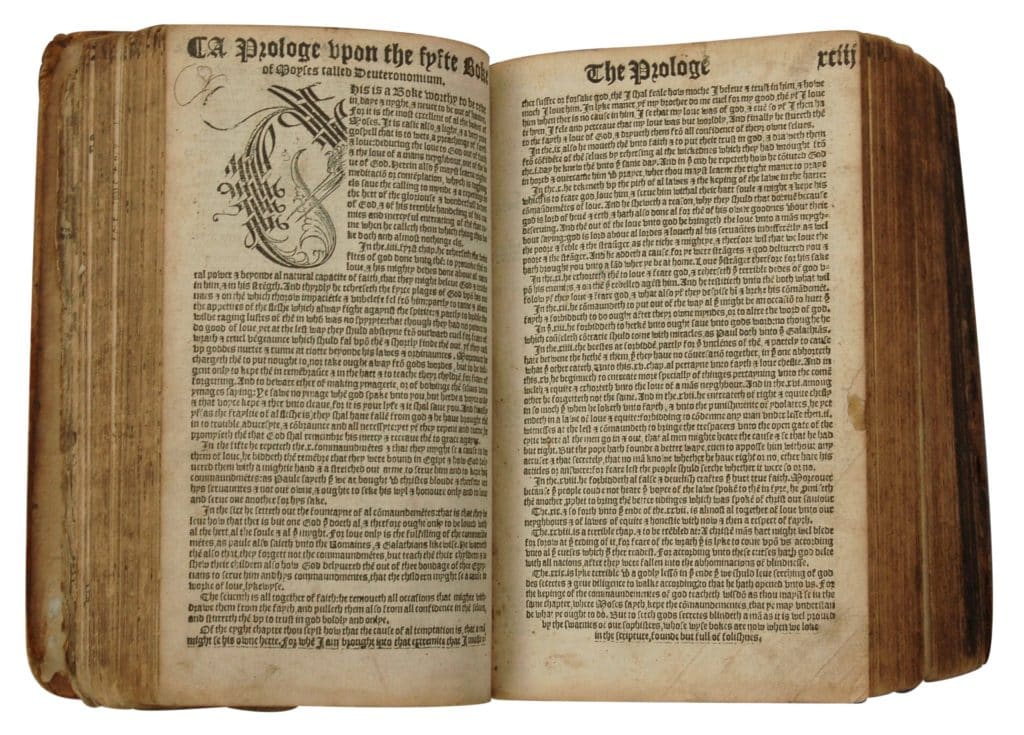

In 1537 John Rogers assembled all of Tyndale’s Bible translations, and filled the remainder of the Old Testament books (Job to Malachi), as well as the Apocrypha, with Miles Coverdale’s translations from the Latin, in a full-Bible English translation with royal approval. Thus, within a year after Tyndale’s death, his dream and dying wish were fulfilled. At the foot of the title page are the words, “Set forth with the King’s most gracious license.” Since Tyndale’s name was still associated with heresy, Rogers used the names of two disciples – “translated into English by Thomas Matthew.” 1500 copies were printed in Antwerp, imported into England, and rapidly sold out. On the last page of the Old Testament are the heavily stylized initials, WT, in a cryptic tribute to William Tyndale.

Later, John Rogers would become the first of almost 300 martyrs under Queen Mary (a.k.a. “Bloody Mary”), who tried in vain to reestablish an exclusive monopoly for Catholicism in England by stamping out all Protestant dissent.

Great Bible (1539)

Only 1500 copies of “Matthew’s Bible” were printed, and there were almost 9000 parishes in England. Reprinting this edition on a large scale would risk the hostility of Tyndale’s opponents. Thomas Cromwell solved the problem, with encouragement from archbishop Thomas Cranmer, by promoting a large-scale revision. The Bible itself would be a very large folio. The published result was called the “Great Bible.” King Henry VIII would be prominently displayed on the title page, as if he had championed the Bible in his native English all along.

As Lori Ann Ferrell says, “This image, then, like all elaborate title-page images from this period, should be read from the top down. To begin: Henry VIII sits enthroned at upper center, taking the place once occupied by the image of God in Miles Coverdale’s Bible… Thus beatified, Henry hands copies of the Bible to churchmen at the reader’s left and statesmen at the right. They in turn pass the books on to the lesser clerics and pious laypeople who populate the middle and bottom of the page.” Even though the translation is still largely Tyndale’s, the tribute to “the most noble and gracious Prince King Henry VIII,” the inclusion of the Apocrypha and a red-letter holy day calendar, and the “Table of the Principle Matters Contained in the Bible” (favoring Anglican Church beliefs) reflect a decided shift into mainstream social acceptance.

The Bible was now a cultural phenomenon. King Henry VIII was vexed because the sacred words “were disputed, rimed, sung, and jangled in every ale-house.” The king began to put fresh restrictions on the use of the Bible. After his death, the pendulum would swing all the way back to a radically repressive regime.

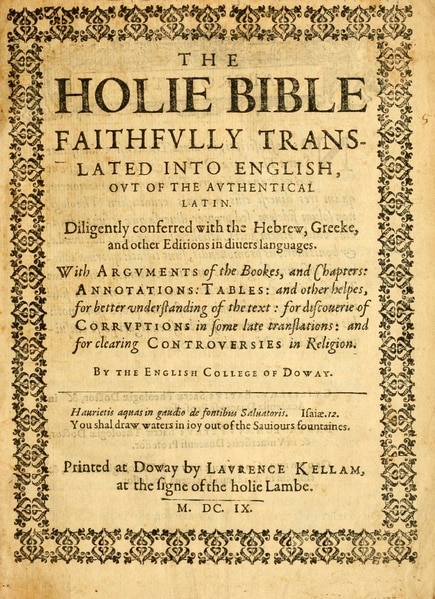

Geneva Bible (1560)

Queen Mary temporarily restored the Church of England to Roman Catholicism. With renewed attempts to burn heretics, Protestants were driven into exile. The Geneva Bible was first published in 1560 and was smuggled from the Continent into England. Geneva was the center of John Calvin’s reforms, and this Bible, intended for the common people, was full of Calvinistic notes. The multitude of helps, maps, and “notes on hard passages” made it the original Bible for Dummies, according to Lori Anne Ferrell. This version also took highly resonating shots at the sinful Old Testament kings. Jehoram, for example “was not regarded, but deposed for his wickedness and idolatry” – words not exactly popular to 16th century European monarchs!

In many respects, however, the Geneva Bible broke new ground. It was the first English version with numbered verses, the first with commentary notes, and the first with Roman typeface. This was the Bible of the Puritans, Pilgrims, and other dissenters. But the Geneva Bible too was eventually printed in England, in 1575 (New Testament) and 1576 (full Bible). Side notes still included a few blurbs offensive to powerful interests in England, but the Book of Common Prayer was added to the front, the Apocrypha included between the Testaments, and the Anglican Psalter-Hymnal added after the Book of Revelation. This Bible was the chief translation of the common people and persisted as such until 1640, long after the King James Version was published in 1611.

The Bishops’ Bible (1568)

As the Geneva Bibles were still streaming into England from continental Europe, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, set out to produce a new version more favorable to Anglican high churchmen. The result was the Bishops’ Bible, issued in the tenth year of Queen Elizabeth’s reign. Although this version became the forerunner of the King James Version, it never really caught on, especially with the masses. Today, copies of the Bishops’ Bibles still in existence are noted for their look of majesty and artistic grandeur, but the translation itself is a bit stuffy too.

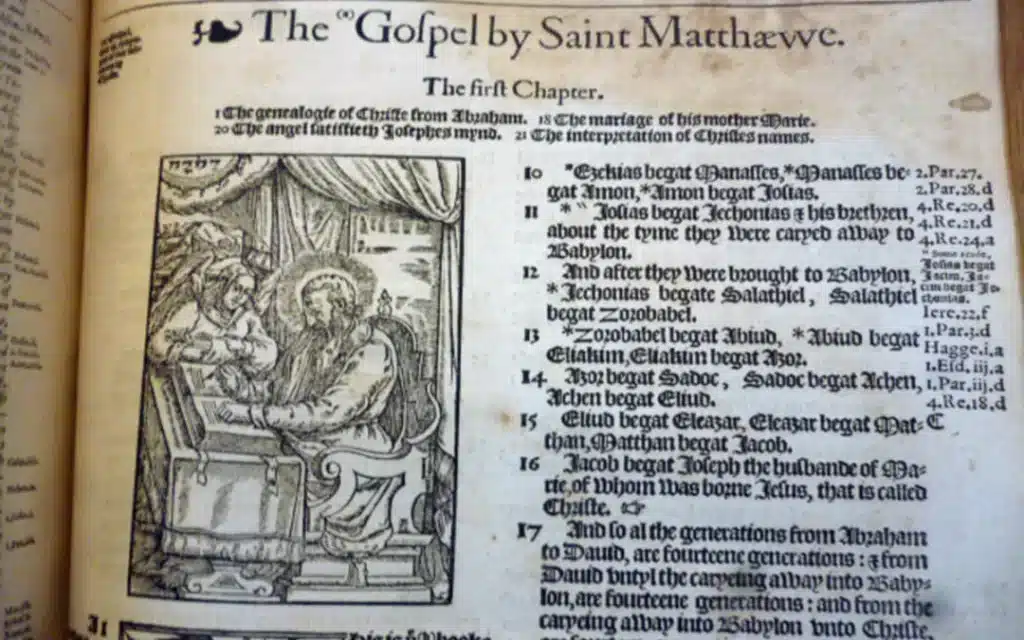

The Douay-Rheims Version (1582)

Roman Catholic leaders, still somewhat in denial about the degree of earlier Bible suppression attempts, were late in the game with an English translation. The New Testament was issued in 1582 in Rheims, France by Catholic scholars associated with the University of Douai. The Old Testament was not issued in full until 1610. The side notes were strongly anti-Protestant. The preface, for example, claims that Protestants were guilty of “casting the holy to dogs and pearls to hogs.” Hebrews 13:17 translates (or paraphrases), “Obey your prelates and be subject to them.” Luke 3:3 says John the Baptist came “preaching the baptism of penance.” On the other hand, the very publication of this version was a tacit admission that Vatican City had lost the battle to keep the Bible out of the hands of the common people.

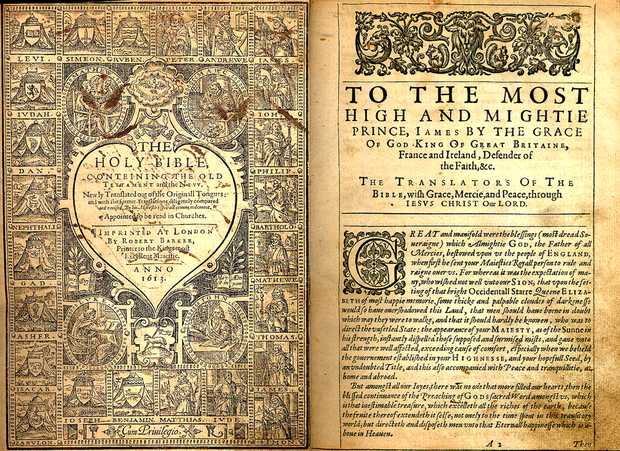

The King James Version (1611)

In 1604 King James commissioned a Bible that is forever associated with his name. The king wanted something that did not have all the doctrinal notes of the Geneva Bible and was more favorable to the Anglican Church tradition. Translated by 47 scholars and printed by Robert Barker in 1611, the so-called “Authorized Version” became, in the words of Lori Anne Farrell, “the best-known, best-selling, most published, most widely distributed… book in the English language.”

John S. Tanner says, “The phrase ‘Appointed to be read in Churches’ announced a fundamental function of the King James Bible. It was intended to be read… aloud, in church… Tyndale’s New Testament, by contrast, was written for individuals reading to themselves ‘round the table, in the parlour, under the hedges, [or] in the fields,’ not for congregations ‘obediently sitting in rows in stone churches’ being read to by the parson or ‘squire at the lectern’ (David Daniell). The Tyndale New Testament was small enough to fit comfortably in the hand. Not so the first edition King James Version. It was a church Bible.”

The KJV, as this edition is often called, is not that of the 1611 version, but rather an edition extensively revised in 1769 for the Oxford University Press. The old spellings were modernized, but to modern ears, much of the old English persists (i.e. “thee,” “thou art,” “ye,” “cometh,” etc.).