When Moses asked God for His name so that he could then tell Pharoah who was commanding him to let the Israelites go, God responded with two words:

I AM

God didn’t need a name like you or I need a name — one that differentiates us from other people. He simply is who He is. There is none like Him, nor will there ever be anyone like Him.

This respect for God’s name has caused a lot of people to refrain from even writing down the name of God. They feel like to do so would bring Him down to the level of a man, debasing Him in the eyes of His creation.

But God has a name. In fact, the several names of God talk about different attributes of His Deity.

When people began to start transcribing the Bible though, they had to write His name down. To accomplish this, they treated His name with the utmost of respect.

Here’s a breakdown as to how that process worked.

Examining the Material Evidence

Much can be learned about the transmission of the Biblical manuscripts from a careful examination of material evidence. Here are a few examples.

- If the scribe used parchment, the manuscript had pinpricks placed in it, so that it could be ruled by lines to mark the horizontal and vertical boundaries.

- In some manuscripts the lines are still faintly visible. In many documents, there are a consistent number of lines per page.

- Early Christians had a decided preference for the “codex” book form versus the scroll. According to one count, Christian codices account for somewhere between 22 to 34% of the total documents for the 2nd and 3rd centuries, yet Christian books amount to only about 2% (codices and rolls).

- Over 95% of Christian copies of the Old Testament writings are in codex form, whereas Jews tended to prefer scrolls – and the same goes for virtually 100% of the extant New Testament writings.

- 127 New Testament manuscripts, including many from the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th centuries, were written on papyrus. The majority were produced on parchment or vellum (leather skin), especially from the 4th century on.

- In some cases, there is a little art work, such as some scribal designs at the end of each Gospel in the Codex Washingtonianus.

- In the Codex Sinaiticus, some red ink headings signaling male and female speakers is differentiated from the brown ink of the sacred text in the Song of Solomon.

Scriptoria

A scriptorium was a room where scribes worked to produce manuscripts. A lector would read the exemplar, and one or more scribes would write down his words. A master scribe or foreman would then make needed corrections.

In some of the manuscript copies, we can actually see where corrections were made. Many of the earliest manuscripts were in fact written by professional scribes or by copyists skilled in preparing documents.

In the middle ages, some monasteries served as centers for copying scripture by hand. In the earliest centuries of the church, there were prominent scriptoria in places like Alexandria, Egypt – the region where some of the best and earliest copies were preserved.

Sacred Names (Latin: Nomina Sacra)

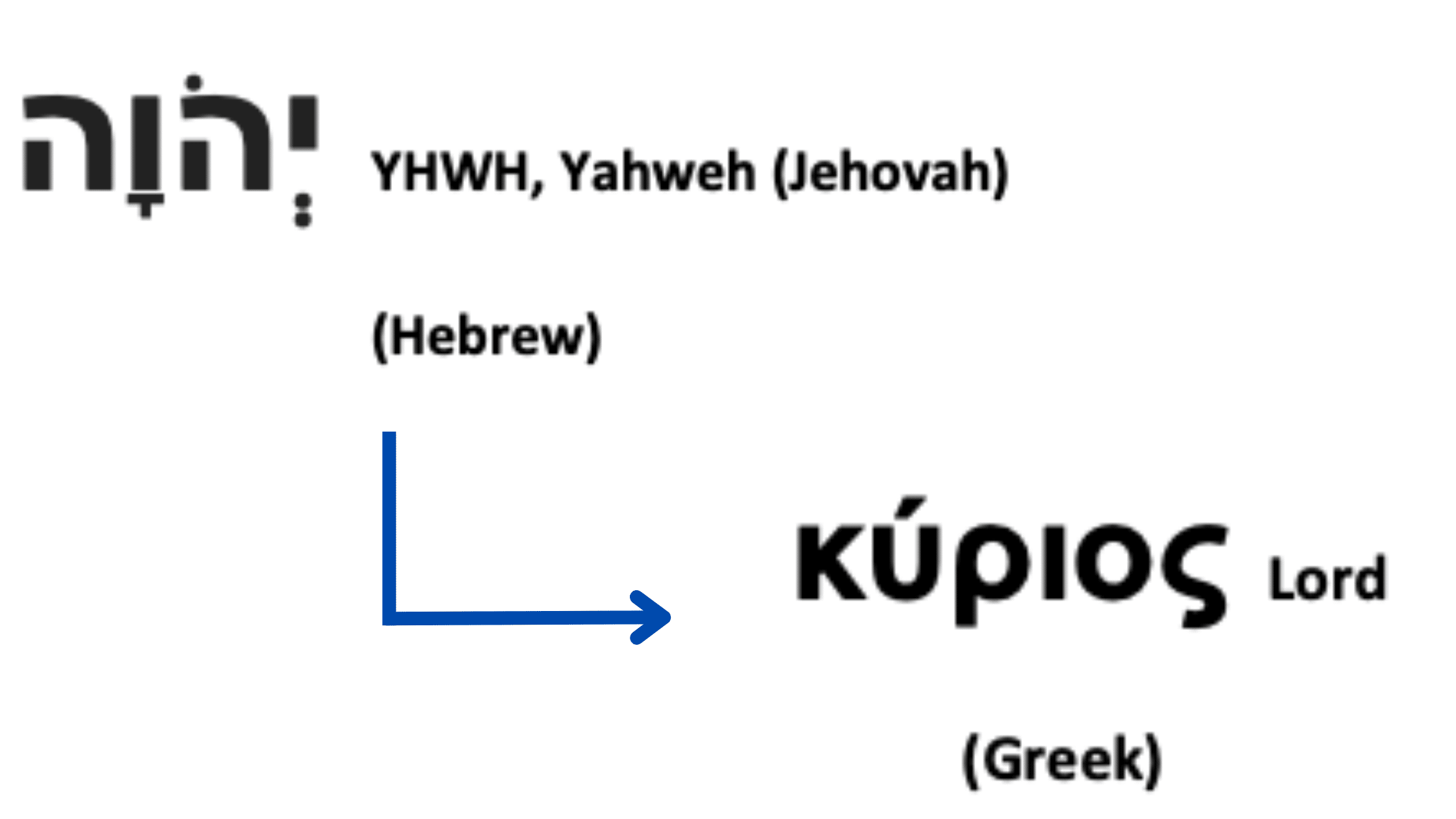

One of the most fascinating and instructive facets of the transmission of the sacred text has to do with how scribes communicated sacred names. In the Old Testament, one name carried special significance – YHWH. Sometimes called the “Tetragrammaton,” i.e. the four-letter word, YHWH is often pronounced Yahweh or Jehovah.

This was God’s personal “covenant” name to the Israelites. Related to the Hebrew verb “to be,” YHWH carried the idea of eternal self-existence. When Moses asked for God’s name, the LORD told him to tell the Israelites that “I AM” had commissioned him (Ex. 3:6, 13-15). God’s holy name was never to be desecrated. A half Egyptian “blasphemed the Name and cursed” (Lev. 24:11). The offender was stoned to death.

In a later development, the Israelites came to substitute the term “Adonai,” or “my Lord,” for YHWH when reading the text. Consequently, several modern English versions honor this tradition by translating YHWH with the capital letters, LORD.

In the third century BC, the Old Testament scriptures were translated into Greek. The version is called the “Septuagint,” which means “seventy” (after an old tradition of 70 translators, and abbreviated with the Roman numerals LXX). For awhile, at least, Jewish scribes put the Hebrew letters “YHWH” even in the Greek text when writing out the sacred Name. Eventually, the Greek word for “Lord” (Kurios) was used.

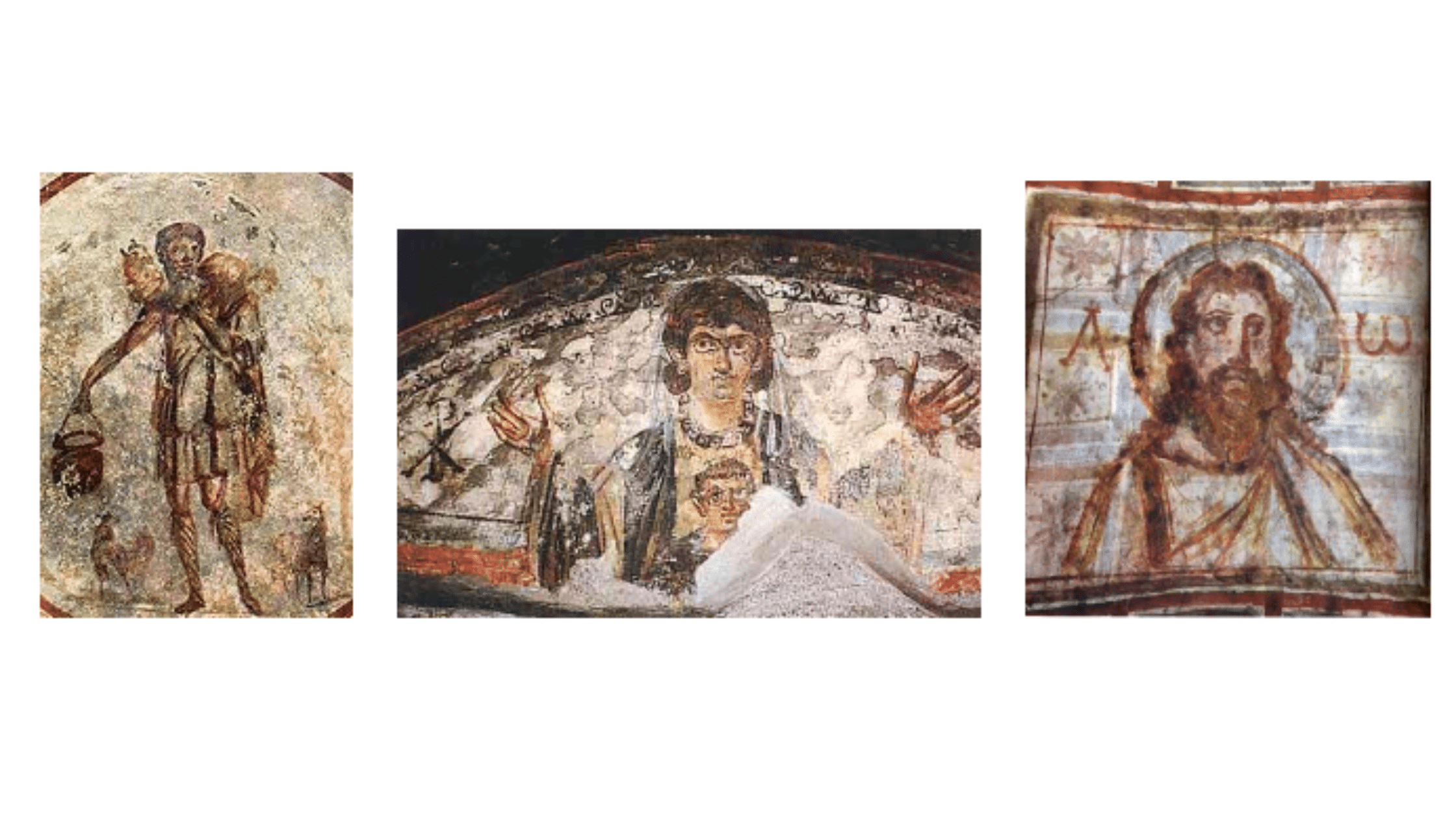

Christians, like Jews before them, tried to avoid idolatrous images in their art. Certain forms became somewhat standardized early on.

The following photos depict the sign of the “fish,” from the Greek ICHTHYS, which forms an acrostic symbol for “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.” Also popular was the Chi-Rho symbol, representing the first two letters of CHRISTOS, or Christ. (The two letters look like an X and a P in English script). This was often written with the Greek letters, alpha and omega, to the left and right of the Chi-Rho.

Sometimes, Jesus is depicted as the Good Shepherd (Jn. 10).

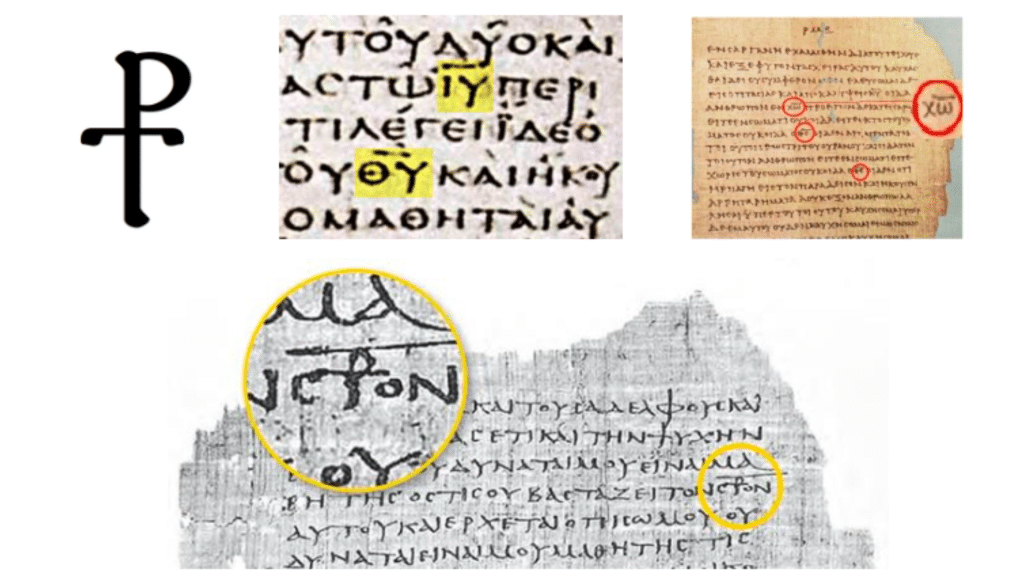

In early Christian documents, especially manuscripts of the New Testament, there was also a way of preserving sacred names, called nomina sacra:

| TERM | GREEK | ABBREVIATION |

|---|---|---|

| Lord | Kurios Κύριος | KS |

| God | Theos Θεός | THS |

| Jesus | Iesous ‘Ἰησοῦς | or IES |

| Christ | Christos Χριστός | IE CHR or CHS |

| Spirit | Pneuma Πνεῦμα | PNA |

| Cross | Stauros Σταυρός | SROS (written with a staurogram, a P with a cross) |

| Crucify | Staurizo Σταυρwmai | SROMAI (with a staurogram, a P with a cross) |

The names were suspended or contracted, and the scribes placed a horizontal bar over the name as a context clue of its holy significance.

Interestingly enough, the forms were standardized early on – possibly as early as the first century. The key nomina sacra abbreviations are in all the early manuscripts, including the very earliest ones.

Ironically, when “lord,” “god,” or “spirit” are not to be intended as sacred names, then the Greek word is spelled out in full. One example is 1 Cor. 8:5-6, where I have emphasized only the abbreviated sacred names in the Codex Sinaiticus – “For although there may be so called gods in heaven or on earth – as indeed there are many ‘gods’ and many ‘lords’ – yet for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist, and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things and through whom we exist.”

In fact, scholars know when an ancient Greek manuscript of the Old Testament was produced by a Christian or Jewish scribe simply by the presence (or absence) of these “nomina sacra” designations.